On the composition of what-we-mean-by-synchrony.

Overview

- Performing “together” in music and dance

- Polytemporality in Music Composition

- Composing the heart, by way of the breath

- Human/Machine Temporalities

Performing “together” in music and dance

As composer-choreographer, we begin from the idea that simultaneity does not exist in the world, and yet, in many fields like music and dance, it is far too important of a concept not to exist. As such, when we discuss how musicians and dancers perform together in time, we must be operating under a different definition of synchronization and simultaneity than the one understood in physics. Importantly, we have come to understand as choreographer-composer the concepts of synchronization and simultaneity have temporal extent – that is, they unfold in a window of time. The question then is how does this extent get determined, such that its constituent parts can be said to be operating “together” under certain circumstances, and “not together” under others?

In fields like telecommunications, they use the notion of plesiochrony, or “nearly in time” to refer to these systems. A system is considered plesiochronus when certain explicit limits have been placed on it, and those limits are determined by looking at the needs of certain tasks. So, if the system is operating within those limits, the tasks are able to be accomplished, and we can say that for all intents and purposes, our system is synchronous.

It is similar in music: synchrony and simultaneity are not merely issues of the limits of our ability to discriminate tiny temporal misalignments, they are matters of aesthetics (and also ethics, but we will leave that aside for now). The criteria by which we judge the temporal acuity of musicians playing the Rite of Spring are not the same as those we apply to a free jazz combo. Now, you might say that we’re simply mistaking synchronization and simultaneity for something else, something aesthetic, but remember our opening point – synchronization and simultaneity don’t exist objectively, they are always matters of aesthetics.

Of course we could say that objectively speaking, this or that group of musicians could play together “tighter”, or this or that group of dancers could be more “together”, and we could use a variety of tools to measure their “togetherness” – but that is simply the application of one value system to a context where it may not belong. The construction of this context is composition and choreography; likewise, the construction of what synchronization and simultaneity mean in a given context are acts of choreography and composition.

Polytemporal composition

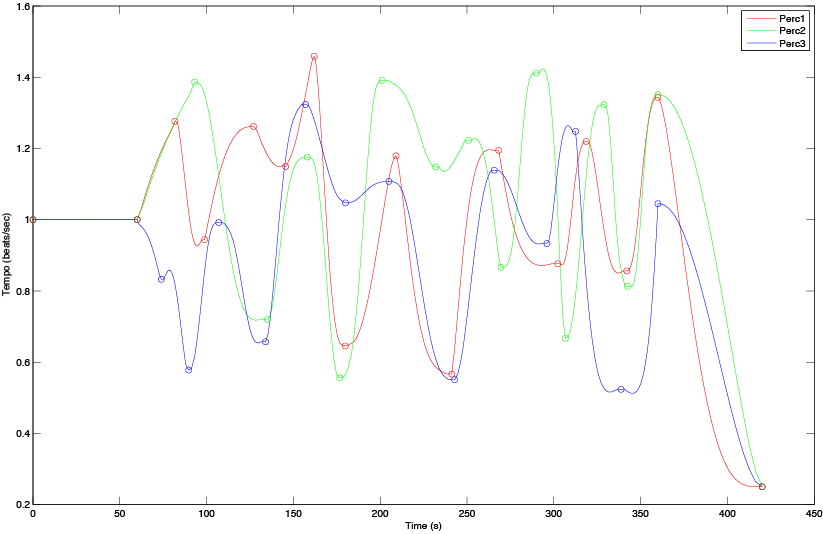

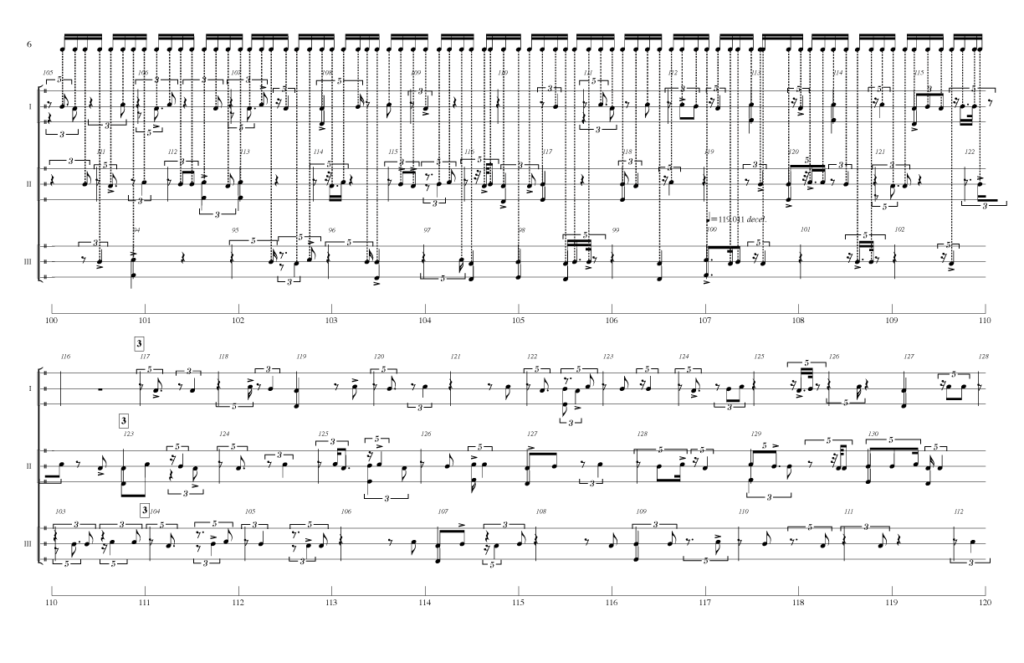

In MacCallum’s compositional practice prior to this collaboration, he experimented with musicians playing in continually-varying tempos, independently of one another. He would construct the “tempo maps” ahead of time so that he knew the relationship of all the parts during the compositional process. See for example the time map for MacCallum’s percussion trio, aberration, as well as the corresponding score:

The creation of these tempo maps let MacCallum compose vertically across the parts, to construct virtual tempos that would emerge out of a complex, polytemporal, varitemporal texture. Below, the score for aberration is annotated to show the emergence of these textures over time:

This approach is also integral to an octet MacCallum composed, delicate texture of time, as seen in the following time map and score:

[slide 10, 11]

Here is the score again, with a line indicating a virtual tempo that emerges through the interlocking of the eight musical parts:

[Slide 12]

Pieces like this require click-tracks to keep the musicians “together” – however, the temporal extent of “togetherness” has been widened considerably.

When we started to collaborate, the idea was that we would replace the pre-composed click-tracks used in John’s prior polytemporal work with the real-time sonifications of electrocardiograms worn by dancers. We imagined that we would decide on a time map for the heart rate of each dancer, and Teoma would then choreograph with the intention of reproducing intentional shifts in the cardiac function of each dancer that more or less correspond to the model. Of course, we know that they won’t correspond exactly, but we were curious about how much correspondence we could expect, given the right kind of training (as discussed in the section on entrainment).

Composing the heart, by way of breath

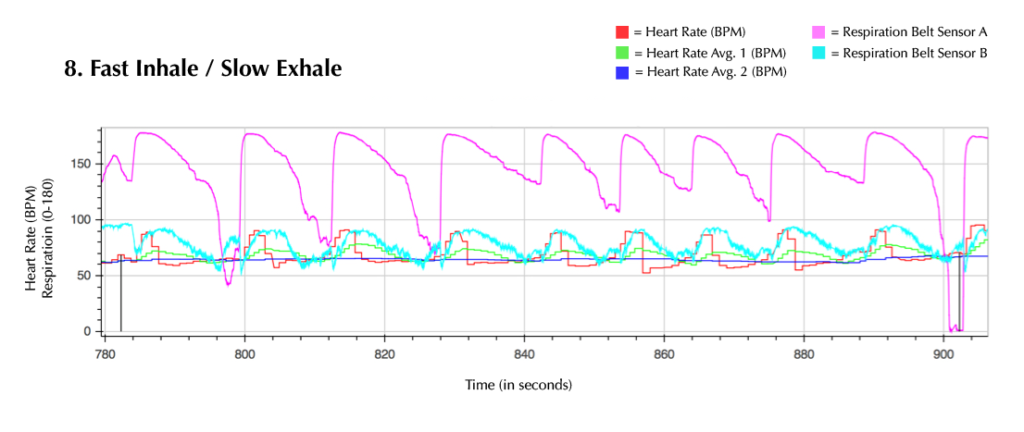

Returning to an example from our early experiential studies on the relationship of respiration and heart activity during a Musical Research Residency at Ircam in the Fall of 2014, we were able to see that patterns in breath correspond to patterns not only in heart rate, but in heart rate variability. Looking at this graph below, which shows the measurements when Teoma was taking very fast, full inhales followed by long, slow exhales, we can see a potential site for “synchronization” in this very specific context.

If you imagine multiple dancers all breathing together in the same manner, it is not the temporal relationship of the peaks of the R waves of their ECGs that matter here, but rather the relationships of their variabilities to one another that communicate “togetherness.” Most importantly, compositional and choreographic strategies must be developed around this basis of what it means to be “together.”

If you imagine multiple dancers all breathing together in the same manner, it is not the temporal relationship of the peaks of the R waves of their ECGs that matter here, but rather the relationships of their variabilities to one another that communicate “togetherness.” Most importantly, compositional and choreographic strategies must be developed around this basis of what it means to be “together.”

These early explorations of breath and heart activity, which were also related to Teoma’s work prior to our collaboration, were hugely important to us during this period; they helped us understand deep issues about the work we were embarking on, but they also made an aesthetic impression.

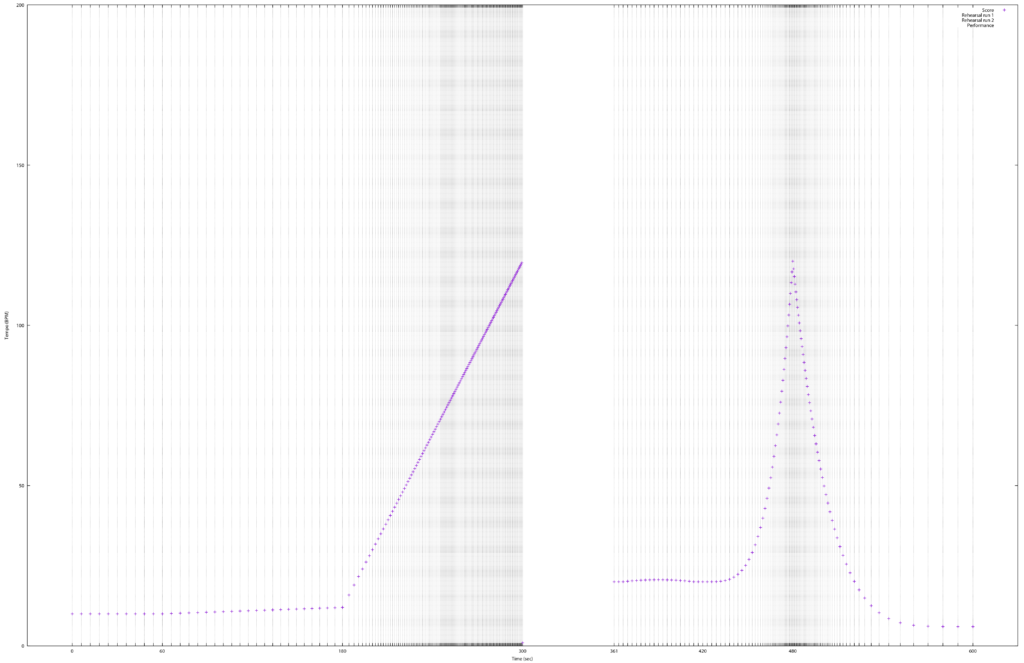

Not long after, we developed a trio for three “breathers” that we performed many times along with a dancer and close collaborator, Laura Boudou. In this piece, we each listen to a click track – precomposed – and we breathe in and out along with it: inhaling with a click, exhaling with the next. All three click tracks follow a similar, but slightly different trajectory (or “time map”, as discussed above).

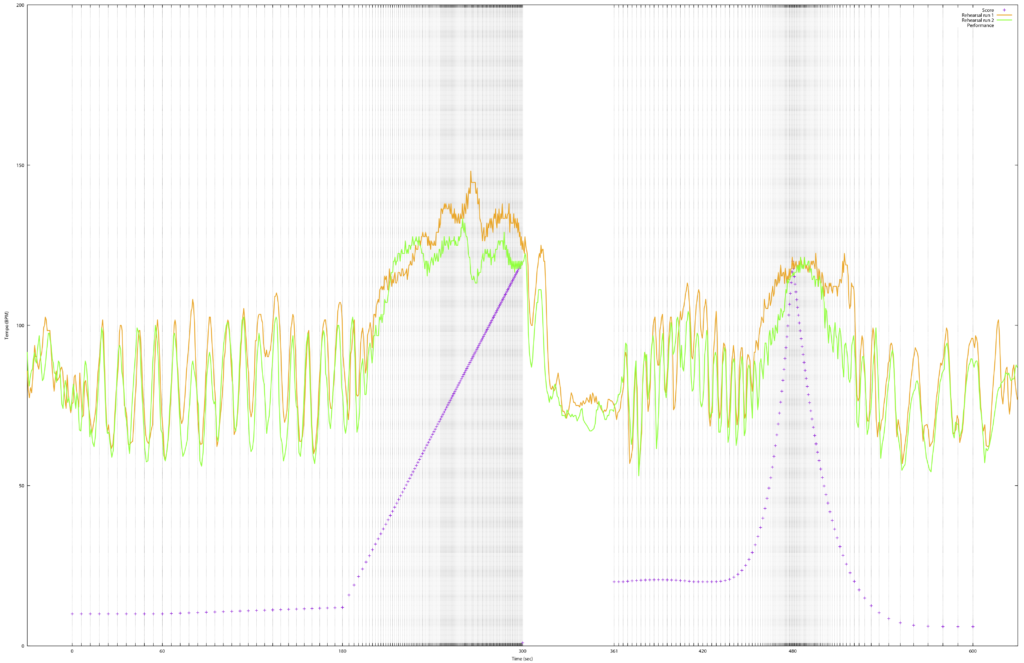

Below is the time map for the second of the three parts. Each vertical black line represents a click (that is, the initiation of an inhale or exhale). The vertical position of the purple crosses mark the tempo of the click-track in beats per minute (BPM) at that moment. In the opening section, each inhale or exhale takes more than six seconds—so, we are breathing very slowly, fully, and audibly.

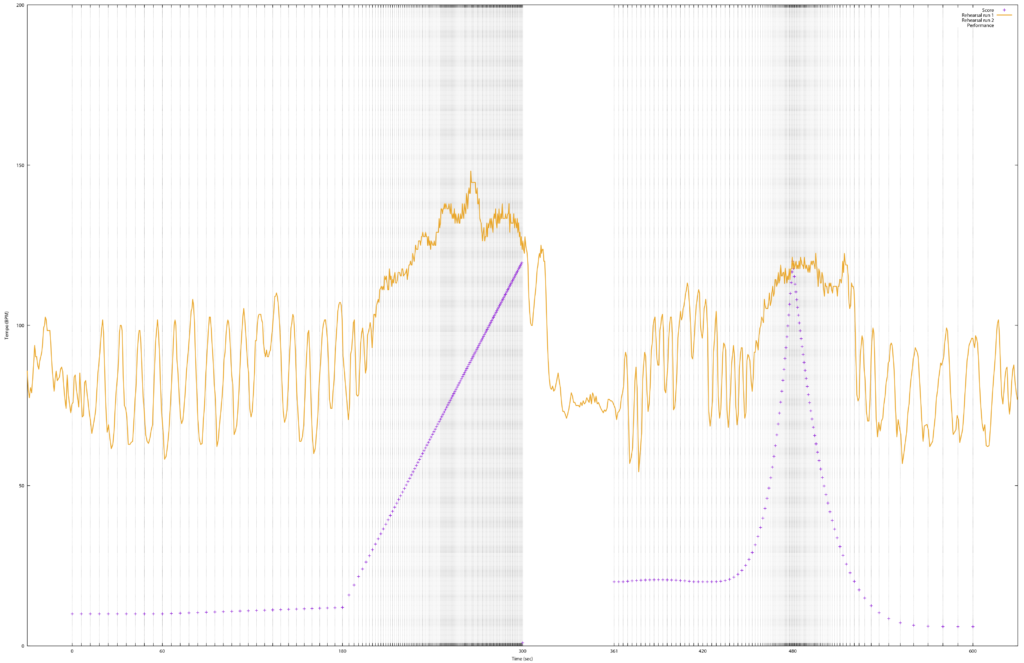

We had Laura wear an electrocardiogram during rehearsal so we could look at the relationship of her heart rate to the tempo of the click-tracks. One remarkable thing to note is the relationship between slow, regular breath, that is, breathing at a fixed tempo, and the wide oscillation in heart rate near the beginning of the piece. As seen in the orange line on the graph below, her heart rate is oscillating between 60 and 100 beats per minute, which, in a musical context, is a huge range. We can also see that the peaks of the oscillations are in a constant relationship to the inhales and exhales, always occurring around the midpoint of an exhale.

This brings up the question of reproducibility – how consistent is this? Turns out, it’s pretty consistent: the green plot is taken from another rehearsal on the same day.

Another question is about the difference between rehearsal and performance; we would expect that the overall heart rate would be faster, and indeed, that’s the case. The blue line on the graph below represents data taken from a performance that night, and what’s interesting is that all the patterns are still there – it looks like the entire graph from rehearsal is simply transposed upwards.

Human/Machine Temporalities

In the breath composition above, what we have is a human listening to a machine-generated click-track, and breathing in relation to it, while a machine transduces and transcribes the electrical activity as it varies with her breath. We can see this apparatus as the projection of the notion of a fixed, constant tempo, from machine-space to cardiac-space. Just as a straight line, when projected onto the surface of a sphere no longer appears “straight” in relation to the Cartesian coordinate system, “fixed-tempo” no longer seems fixed when projected onto bodily processes.

Back to our time at Ircam, we were attempting to answer this question about reproducibility – to what degree can a dancer reproduce the same shifts in tempo in heart rate over time while executing the same choreography? As discussed in relation to Performance Study 1, we built a “score”, a time map of what one’s heart should do if it were a controllable, mechanical device, that would serve as our reference, our “ground truth”. Teoma choreographed a short solo on herself and a dancer we collaborated with at the time named Bekah Edie. The choreography included a number of explicit instructions about how to breathe at different moments throughout – we were also interested to know how much breath would affect heart rate and heart rate variability during complex movement. We were pleasantly surprised by the consistency with which the two dancers, during numerous runs of the solo, were able to reproduce intentional shifts in heart activity over time. At least that’s the story about reproducibility that we were satisfied with at the time…

The problem is, that back in 2014 we had not yet interrogated the processes by which we judged these plots to be similar – to each other, and to the model. We talked a lot about how the juicy musical material was most certainly contained in the discrepancy between the real data and the model, but in such a way that relegated difference to the role of ornamentation. We hadn’t yet come up with a way of talking about the difference between these two temporalities in a productive way, a way that begins from the standpoint that measurement of the heart is an act of composition and choreography; that measurement of the heart is dissection; and that once removed, it has to be considered on its own terms, not with respect to an archetype from another context.

The following section on relationality marks a turning point in our understanding of how to collaborate with the-thing-we-call-the-heart, beyond tactics of control and representation.